IBWOH: Chris Carlisle.

Summary: A five-and-one-half-hour survey of the lands east of Hutson Lake and Lake Hollow Man, following the north-south line of the old logging trail between the two lakes. Several long, narrow fields, planted in ryegrass, are interspersed with prime stands of mixed bottomland forest, and with a network of wooded sloughs and small lakes. Dominant tree species are water oak, swamp chestnut oak, sweet gum, water tupelo, baldcypress, and spruce pine. The eastern edge rises to mature upland pine forest, eventually giving way in its turn to a much younger, monoculture pine plantation on private property.

We have surveyed much of this area before, but the eastern edge is new to me, and I was well pleased with the quality of the mature bottomland forest I often found myself in. The sloughs and small lakes in the area are on the rise, due to recent heavy and sustained rainfall.

After a long drive through the dark and the intermittent rain, I began my hike at 6:30. Dawn came around twenty minutes later. It was muggy, and as the temperature rose to near 70 degrees (Fahrenheit), I was soon sweating under my flannel shirt. The rain held off for the duration of my hike, though the sun only occasionally shone through a tear in the blanket of clouds.

Most all the usual avian suspects were present. The area is infested with red-headed woodpeckers. At times it was difficult to hear any other birds over their ubiquitous rrruuuuukkkk's, the resident blue jays demonstrating their entire repertoires, and the screaming of Cooper's hawks. Pairs of wood ducks whistled at whiles through the trees overhead. As for Hutson Lake itself, cormorants have laid sole claim to its waters, at least for the day.

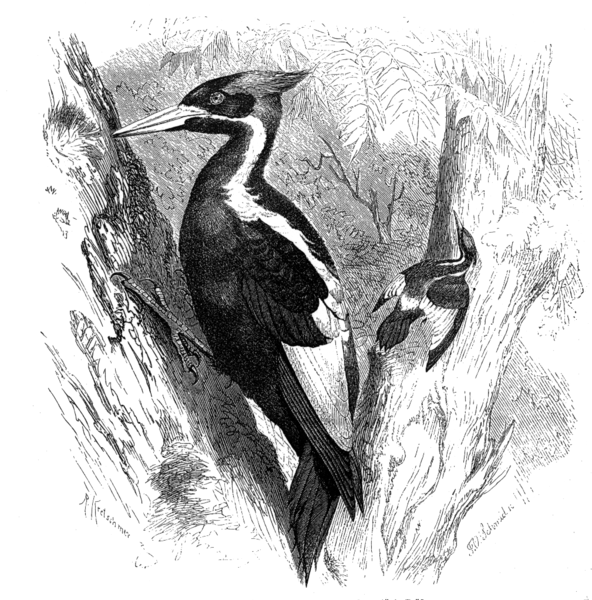

Conclusions: I heard no kents or double-knocks. Despite the leaf-fall, which has opened up much of the forest to human eyes, I found no peeling or excavations that I felt could be considered diagnostic of ivorybill feeding behavior. I must admit to feeling discouraged. More than once, I found myself muttering, "Where are they? They should be here." I may have exhausted my search efforts in this particular area, which due to the quality and extent of habitat, I have long considered prime ivorybill real estate. There were signs of human hunting activity, however, in the form of spent shells and shell boxes; but I encountered no hunters personally, and the sounds of gunshots were to the west of the river, and farther east, on private property.

I may return to the area in January, if only to install a game camera, which my brother Brian feels could be an important component of our overall search effort; and I have begun to come around to his thinking on the matter.

Still, the question remains: where are the ivorybills?

Summary: A five-and-one-half-hour survey of the lands east of Hutson Lake and Lake Hollow Man, following the north-south line of the old logging trail between the two lakes. Several long, narrow fields, planted in ryegrass, are interspersed with prime stands of mixed bottomland forest, and with a network of wooded sloughs and small lakes. Dominant tree species are water oak, swamp chestnut oak, sweet gum, water tupelo, baldcypress, and spruce pine. The eastern edge rises to mature upland pine forest, eventually giving way in its turn to a much younger, monoculture pine plantation on private property.

We have surveyed much of this area before, but the eastern edge is new to me, and I was well pleased with the quality of the mature bottomland forest I often found myself in. The sloughs and small lakes in the area are on the rise, due to recent heavy and sustained rainfall.

After a long drive through the dark and the intermittent rain, I began my hike at 6:30. Dawn came around twenty minutes later. It was muggy, and as the temperature rose to near 70 degrees (Fahrenheit), I was soon sweating under my flannel shirt. The rain held off for the duration of my hike, though the sun only occasionally shone through a tear in the blanket of clouds.

Most all the usual avian suspects were present. The area is infested with red-headed woodpeckers. At times it was difficult to hear any other birds over their ubiquitous rrruuuuukkkk's, the resident blue jays demonstrating their entire repertoires, and the screaming of Cooper's hawks. Pairs of wood ducks whistled at whiles through the trees overhead. As for Hutson Lake itself, cormorants have laid sole claim to its waters, at least for the day.

The predawn forest.

A woodpecker totem-tree.

Rye grass field.

Heavy scaling and some excavation to a dead snag.

I had a Milky Way bar, in tribute to the memory of Jack Kuhn.

Another woodpecker totem-tree (right).

El Tenedo del Diablo -- Devil's Fork.

One of many wooded sloughs in the area.

The forest wears the rags of summer like a mourner's cloak.

I spied beyond this grove another monolith -- a titan cypress. High water prevented me from getting close enough for a photo.

Loblolly pines, a sure sign that the bottomland forest is ending.

Hollow Man's lake has engulfed him.

I may return to the area in January, if only to install a game camera, which my brother Brian feels could be an important component of our overall search effort; and I have begun to come around to his thinking on the matter.

Still, the question remains: where are the ivorybills?

.jpg)